The way grants are selected for funding is highly inefficient at many levels, induces scientists to use gaming strategies, and tends to exclude scientists who are also very valuable to science.

I got my first big investigator-initiated grant from the NIH on my first try. It was like an experiment that works the first time; you do not learn much about the result. I had very little experience writing grants and almost everyone said that it would not work because of my status, as basically a post-doctoral fellow. I was not deterred because I believed in the system, that it would value science more than status.

As a first-time applicant, I could submit the same project to both the NSF and the NIH. At that time, the probability of the NSF funding the grant was much lower than the NIH. The NSF review came first and my grant was not funded. But that was the first and the only rejection letter I have read with delight. I could barely contain the refrain running through my mind: The NIH is going to fund me! The NIH is going to fund me! It did, and my belief in the system soared. I remember writing a glowing letter in response to a feedback request from the NIH, emphatically stating that the system worked, very well, thank you. That’s how I felt in 2001 about the mechanism for selecting grants for funding within the traditional system.

Years 2001 to 2005 were my most blissful and productive period. I published the first of what I consider to be my two most creative papers; one that combined a little bit of physics and a little bit of chemistry in the context of cell-cell contact that is of great significance to animal development. I was heady with the data in that paper and in others I published in that period. Sure, I had received a couple of rejections by then but felt that they were par for the course and renewing my grant or getting another one was imminent. Instead, the rejections piled on, almost two a year, for the next five years.

Initially I was intent on addressing the comments of reviewers or colleagues with the best data possible within my capacity. When that did not work, I obsessed over dissecting the comments from every angle, convinced that there is a code for success that I needed to crack or at least stumble upon. When I started experiencing déjà vu moments — getting the same comments although the issues were addressed to the best of my abilities — I realized that I had exhausted dealing with the issues raised in the reviews and the remaining ones were out of my control. As a consequence I simply stopped taking the reviews seriously, if I read them at all. Then in 2010 I got funded again, with a smaller, two-year NIH grant. Reading the good reviews this time, I felt little joy and mostly relief with a horoscopic refrain going on in mind: But for the favorable alignment of chance and circumstance.

In 2013, I published my other most creative paper, showing evidence for the involvement of ultradian oscillation of cell-cell contact in long-term memory formation. When the grant application based on this paper was not funded and I realized that my third most creative paper had no chance of being completed in the manner I desired, I stopped writing grant applications and started analyzing the mechanism that failed to regularly fund a scientist like me. I believe that I am a good scientist and a very committed one at that, but these qualities were not my justification for expecting support.

These were my reasons: (1) I was leaving many a conversation wondering how that person managed to get so many grants; and (2) I believe that the data in my grant applications have the best potential for resolving many of the discordant or ‘controversial’ issues in my field that are of significant relevance to biology and human health. I am not being cocky or vain, just confident. I suspect that you would feel the same way if you had spent more than 25 years at the bench, conducting experiments on the same subject, and personally analyzing all raw data generated in your lab, and are convinced that you have data that are useful for the field, but cannot get funds to pursue them further. It is hard not to feel jilted by the mechanism.

By mechanism I mean the ways and means by which grants are selected for funding in the traditional system. You can think of it as the engine that uses fuel (funds) to do work (produce data). The basic operating principle of this mechanism is that grants selected for funding provide the best data and the most rapid path for progress in our knowledge of a phenomenon. As a consequence, funding agencies spend considerable effort and resources to develop selection criteria and properly apply them to identify research areas and projects for funding.

Although I have doubts about the efficacy of some of the criteria used by funding agencies, I have the highest regard for the sincerity of motivations behind all of them, be they governmental or private. I have no doubt that the agencies are doing the best they can within the confines of the traditional system. However, even when functioning under the best of conditions and intentions, the traditional system’s mechanism has three basic problems.

a. Highly Inefficient

The first and the foremost problem with the mechanism is that it is highly inefficient. As I argued in the previous essay, at least about another 50 to 60% of the grant applications could be funded, the fraction considered to be sound enough to be discussed by review panels. The current funding rate across major funding agencies is about 10-20%, which means that 40 to 50% of eligible grants are rejected at each funding cycle (generally 1-3 times a year). I think that this rejection level amounts to an enormous waste for two reasons.

The first reason is that rarely, if ever, do projects unfold exactly as proposed in the application simply because it is almost impossible to predict every result of every experiment to be conducted in the next 4-5 years. That means grants are rejected (or funded for that matter) based on proposals that may not even materialize. The second reason is that what actually does materialize could be totally unexpected (i.e. data that were not predicted) or even be unrelated to the issue the experiment was designed to address and yet be very significant. This is how many important or breakthrough results, both big and small, are often obtained. This has happened many times in my own research, when unexpected results took me in new directions.

I am not talking about those very rare, truly serendipitous results that occur by chance or accident. I am talking about those that occur once a course of experiments or studies is pursued for the first time, which is what every grant application represents. Just imagine how much we might have already missed from all those projects that were scientifically sound but were not funded over the past several decades. I now have serious doubts that it is even possible to reliably predict the significance and impact of the majority of grant applications in terms of actual outcomes for a field measured over long periods of time.

That does not mean that all the efforts going into selecting 10-20% of the grants for funding are of questionable value. No. They are indeed very valuable but mostly to one part of science, the part composed of well-established data. To understand this point, consider the fact that an important criterion for selecting grant applications for funding is a high probability for obtaining the results predicted, which is in general possible only with well-established preliminary data and not with very new, frontier data. In other words, the grant selection mechanism is good at establishing strong fields of research but not at expanding these fields. Ideally, both well-established and frontier data need to be supported for robust and rapid progress in any research area.

There are programs earmarked for supporting frontier science (Pioneer grants, R21, Innovation grants, etc.) with instructions for reviewers to relax the selection criteria and go for big picture concepts based on logic or insight. But in practice it is not that easy. How can the reviewers relax criteria when the success rate for these grants is worse than the regular grants? How can they distinguish a truly path-breaking frontier grant from the one going nowhere when there is not enough evidence (data) to rely on?

If there is one thing I have learned over 30 years of research, it is to be very cautious when I think ‘I got it’ because often it turns out to be ‘stupidity,’ and I relied upon experiments and data! I believe this kind of caution is the reason why reviewers consciously or subconsciously end up relying to the same extent on the same criteria they use for other type of grants (data, position, institution, publications, predictability, fashion, etc.). Thus, despite well-intentioned efforts by the funding agencies, frontier sciences — essentially sciences at the edges or fringes of a field — are not really supported by the mechanism. Therefore, much of the data that are frontier or less well-established are essentially wasted in the traditional system.

Another contributor to inefficiency is what I call ‘waste within a waste.’ The mechanism is biased in favor of grant applications that are based on publications for the simple reason that it means the preliminary data have passed a certain level of scrutiny and acceptance in the field. However, a significant amount of data is generated specifically for the grant application in order to provide the basis for the experimental design proposed and suggestive evidence for results predicted. These data are unpublished. As the grant applications go through cycles of resubmission, to the same or different agencies, more and more grant-specific unpublished data are generated, mostly to address reviewers’ comments. The data are accurate and meaningful in a limited sense but are not cogent or strong enough for publication.

Just imagine the magnitude of these wastages when only 10-20% of the grants are funded. When in one year alone (2013) about 90,000 applications were rejected by the NIH and NSF, what would be the number if all the applications to all funding-agencies over the last few decades were added up? The number would be staggering. Yes, these numbers would include some redundant applications that do not contain extra, unpublished data, but repeat applications generally do. Imagine further how much time and resources of researchers, grant administrators (at both institutions and funding agencies), and reviewers are wasted in generating unpublished data and processing unfunded grants. Therefore, to me rejections of scientifically sound grant applications are not only wastage of unrealized opportunities but also of unpublished data contained in these grants.

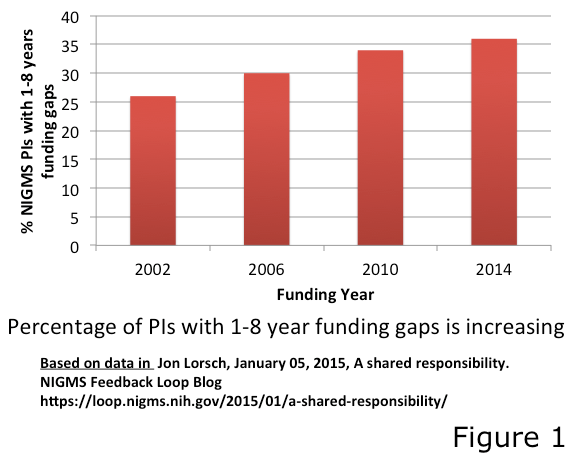

Yet another contributor to inefficiency is the underutilization of time, talent, and resources of scientists when there are funding gaps or when funding is permanently lost. Figure 1 shows the funding profile at one of the institutes of the NIH. More than 35% of even successful researchers experience a 1-8 year funding gap between projects. In general, the first year after grant expiration some research continues because some funding agencies allow rollover of a fraction of residual funds (e.g., 25%). After that, research will be basically suspended unless alternate funds are secured from other sources. Many institutions provide what are called ‘bridge funds’ to support experiments necessary to restore extramural funding. However, these funds are relatively too small, available to very few in an institution, and not all institutions are able to maintain such programs. Thus, with a 10-20% funding success rate, most institutions at any given time will possess a significant number of scientists in funding gaps and most of their time, resources, and talent are being wasted.

Yet another contributor to inefficiency is the underutilization of time, talent, and resources of scientists when there are funding gaps or when funding is permanently lost. Figure 1 shows the funding profile at one of the institutes of the NIH. More than 35% of even successful researchers experience a 1-8 year funding gap between projects. In general, the first year after grant expiration some research continues because some funding agencies allow rollover of a fraction of residual funds (e.g., 25%). After that, research will be basically suspended unless alternate funds are secured from other sources. Many institutions provide what are called ‘bridge funds’ to support experiments necessary to restore extramural funding. However, these funds are relatively too small, available to very few in an institution, and not all institutions are able to maintain such programs. Thus, with a 10-20% funding success rate, most institutions at any given time will possess a significant number of scientists in funding gaps and most of their time, resources, and talent are being wasted.

I can vouch for that kind of waste, because I lived in a funding gap for about four years. First, my capacity was reduced because I lost people working for me. Second, I personally went from running 3-4 experiments a week and working 12-15 hours a day at the bench to 1-2 experiments a month and spending most of the time in the office, figuring out the cheapest way to do experiments and writing one unsuccessful grant application after another.

The data set underlying Figure 1 does not include researchers who were unfunded, not able to renew their grants in the previous 8 years, or did not reapply in the previous four years. These excluded researchers are basically forced to abandon their projects, any unpublished data, and empirical resources generated by them or provided to them by their institutions. Unaware of this abandoned research data, other researchers follow in the same unsuccessful path and duplicate the wasted effort. Eventually, researchers who are unable to obtain funding for some time (most no more than 2-5 years) turn to or are assigned other jobs for earning a living, thereby permanently wasting talent and resources they had acquired.

The flip side of all these unfortunate wastages is the waste in the many labs that are flush with funds. While limited funds forces people to be more careful with resources when designing and conducting experiments at the expense of time that is in abundance to them, generous funds or endowments allows people to be lax in planning experiments and using resources because they are worried about wasting time. Both responses are extreme, but they are natural human behavioral tendencies given the way the system works.

As you can see, inefficiency is a major problem with the traditional system’s mechanism for selecting grants for funding. It wastes opportunities by rejecting a large number of grants that could be funded, wastes a large amount of unpublished data and all the resources consumed generating them, and wastes the time, resources, and talent of a large number of researchers who are without funds at any given time.

b. Easily Gamed

The second basic problem with the traditional system’s mechanism for selecting grants for funding is that it is easily gamed. I use the word ‘gamed,’ ‘game,’ or ‘gaming’ here to refer to strategies people use to enhance their chances of getting funded without being fraudulent. To me it is a problem of the mechanism and not of the researchers because when competition becomes intense, out of necessity or design, and reliance on data alone becomes risky, people can be expected to do anything within the bounds of accepted practices in order to succeed and survive.

For example, since grant applications have very little chance of getting funding if they are not based on publications, researchers can be expected to publish as many papers as possible in any journal that accepts them. In response, journal publishers can be expected to capitalize on this demand and make money by accepting more papers for publication, either in existing journals or in new journals. This mutually fueled frenzy has come to pass with an almost exponential proliferation in journals publishing scientific papers. Not surprisingly, the quality and depth of published papers is now very heterogeneous and raises significant problems for grant review.

Many reviewers try to deal with the problem of heterogeneity by weighting publications by “impact factor” (how many times a journal’s average paper is cited in the literature). But the impact factor is a problematic measure, as it favors current trends (fashions) and well-established areas of research. This bias is further skewed by the peer review system. Since a large number of applications are evaluated every cycle, each reviewer is individually assigned a group of applications. While a reviewer might be able to understand the proposed research in all the assigned applications, very rarely, if ever, will a reviewer have intimate knowledge of the scientific and technical aspects in all of the applications. To overcome this deficiency, many reviewers rely on secondary summarizing sources (review papers). However, these sources are also biased in favor of fashionable trends or popular models in the field.

Researchers wise to this practice tend to write grant applications that fit popular models or fashionable trends. They also tend to write applications that are simplified such that even someone outside the field can understand the primary research data. There are two negative consequences to these practices. One, the opinions of people not conducting research on the subject trumps those of people who have often spent years or decades studying it. Two, researchers intentionally or inadvertently (perhaps most likely desperately) tend to simplify in a manner that inflates the probability of obtaining the predicted results, or the significance and impact of these results, with the hope of increasing their chances of getting funded.

Gaming also intrudes in numerous ways under the category of ‘grant craftsmanship.’ For example, the metrics reviewers are instructed to employ to rank grant applications are numbers imposed on subjective assessments of impact, significance, or innovation. That they are indeed subjective is indicated by the fact that very rarely do all reviewers apply the same number to all these factors on the same application (even when ‘adjustment’ of values is allowed by funding agencies when panel members discuss applications). The assignment of these numbers is vulnerable to influence, even manipulation, by the applicant or the reviewer. Furthermore, people who are skilled in the art of writing or good in grasping big picture ideas can better communicate the significance of their projects even though the project will be terrible in experimentation.

Another example of grant craftsmanship that can influence or manipulate assessment is the topic. Certain topics evoke higher consideration in the mind of the reader (e.g., dementia or cancer), such that they can elicit allowances on empirical deficiencies or higher scores on significance or impact assessment. As a consequence, researchers tend to link their subjects of research to such topics, however remote or indirect it can be, with the hope of increasing their chances of getting funded. A third example of attempting to influence review is researchers seeking collaborators based on their position or previous publications, irrespective of their actual contribution to the research proposed in the grant application.

A fourth example of influence is what I call ‘familiarity factor.’ People who serve on review panels have an unfair advantage over others, as they will have better information on how such panels work. Consider also the situation of a reviewer who has to choose between two equally good grants. One is from someone he knows well or has an established position in the field while the other is a relatively unknown from a less-reputed institution. Which one do you think most people would choose for funding?

It must be already clear to you that the gaming issues I am talking about are not the pernicious or fraudulent kind that are easier to pinpoint and police. In fact, the funding agencies have already done a good job minimizing such fraud. The gaming issues I raise are very difficult to eliminate because they are based on the natural tendencies of people given the way the mechanism works. The unfortunate consequence of all these natural gaming tendencies is that the traditional system’s mechanism tends to reward researchers who embellish, hype, or select their data and penalize researchers who simply present data in the form they are obtained.

c. Very Exclusionary

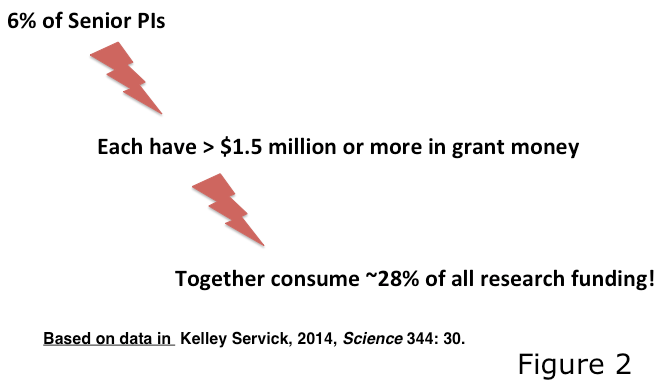

The third problem with the traditional system’s mechanism is that it is very exclusionary. Scientists running large laboratories are favored, as they have the resources and people to publish more papers in high-profile journals and generate a large amount of data per unit of time. Figure 2 shows that such scientists (generally senior scientists), constituting just 6% of funded researchers garner 28% of research funds from the NIH, which translates to about a 5-fold advantage over other scientists. Scientists in reputed institutions or with impressive titles and positions are also favored, as these features are taken as indicators of a safe return on the investment of funds, both by grant reviewers and funding agencies. Reverse discrimination is also possible: denying funds to a scientist from a wealthy institution despite deserving research data.

The third problem with the traditional system’s mechanism is that it is very exclusionary. Scientists running large laboratories are favored, as they have the resources and people to publish more papers in high-profile journals and generate a large amount of data per unit of time. Figure 2 shows that such scientists (generally senior scientists), constituting just 6% of funded researchers garner 28% of research funds from the NIH, which translates to about a 5-fold advantage over other scientists. Scientists in reputed institutions or with impressive titles and positions are also favored, as these features are taken as indicators of a safe return on the investment of funds, both by grant reviewers and funding agencies. Reverse discrimination is also possible: denying funds to a scientist from a wealthy institution despite deserving research data.

The foremost problem with that manner of disbursement of funds is that it leads to uneven development of a field. Areas that are the focus of these senior scientists develop well at the expense of other related fields, which is not good for science. A more distributed development would not only create more opportunities for synergy between the well-established areas of science but also expand the sources for frontier data.

What is also not good for science is data not being generated freely and in the most efficient manner. This is not possible when only a small number of researchers consume a large amount of available funds. With a 10-20% grant application success rate, the mechanism is effectively reduced to a zero sum game. In such a situation, what the well-endowed scientists are accomplishing is counteracted by what is excluded from unfunded grants and suppression of collaborations.

I am very much concerned about the exclusion of small laboratory scientists. These scientists, who tend to be personally involved in the generation of primary research data and have considerable knowledge, competence, and experience, are being forced out of the traditional system by the way its mechanism operates. Also in jeopardy are scientists having novel or adventurous ideas, since the traditional research system favors safety over creativity. Perhaps the greatest exclusion is the deterrence of young scientists. Due to the high emphasis on science in K-12 education, a large number of students seek higher levels of education with a desire to conduct scientific research. They quickly learn in college that their chances of earning a good living doing what they love is forbidding, and as a result, choose more reliable, non-research-based career paths.

Some might consider the mechanism for selecting grants in the traditional system ‘weeding,’ as one colleague put it. Well, for one thing, yesterday’s weed could be today’s grain, as the history of agriculture would attest. For another thing, that attitude is ripe with arrogance. One can determine whether an experiment is well done or appropriate for the question posed, but how can one be sure a data set is worthless in the long run? Think of Mendel. He would have been considered a weed. In fact, he was, for more than 35 years. Fortunately, he was able to publish the paper, enabling the rediscovery of his work even after his death. Most scientists today will not be able to publish without funding and their chances for rediscovery, or even a second chance at research, are close to zero.

I believe that what is good for science is not a mechanism that is based on negative screening and elimination but one that is based on positive screening and inclusion. The traditional system used to be inclusive and supportive when the research enterprise was small but has become harsh due to the rapid expansion in the volume of both scientists and data.

In designing this new system for research, I sought to make the new mechanism highly efficient at every level, resistant to gaming strategies, and very inclusive so that even the most novel, poorly understood, and riskiest projects are supported. The approach I took was to do what is necessary to obtain the best product, i.e., data. It is analogous to designing an engine using the output for assessing how well its components work.

Therefore I needed to also address the data problems in the traditional system, which I discuss in the next essay, essay 6. In the subsequent essay, essay 7, I will present my criteria and guidelines, as well the reasoning I used to design the new system for research that overcomes all the funding, mechanism, and data problems found in the traditional system.

Cedric